Click here for a downloadable PDF (2.1MB) of this report.

What is RTA?

What is Transit Oriented Development?

What is Joint-Development TOD?

Why Transit Oriented Development?

RTA’s Community Planning Initiatives

RTA’s TOD Initiatives

RTA Supporting Community-Based TOD Initiatives

Land Use Keys

Transportation Keys

Technical Discussion of Recommended TOD Guidelines

Density

Mixed-Uses

Pedestrian Orientation

Access and Connections

TOD Site Survey Worksheet

Reference and Bilbliography

Appendix: Federal Transit Administration Guidance and Regulations for Transit Oriented Development and Federally Funded Joint Development Improvements

Introduction

In a proactive planning effort, the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) is developing guidelines for Transit Oriented Development (TOD) projects within their service area. The ultimate goal of these guidelines is to promote vibrant and livable station areas that benefit RTA customers and the surrounding community, as well as promote the use of RTA as a primary means of transportation.

These guidelines are intended to serve as an important step in an evolving process for proactive planning around RTA stations resulting in TOD projects that support the goals of the community. The guidelines establish an avenue for public involvement in the planning process, allowing citizens, decision makers, developers, and the RTA to collaborate on community objectives, understand the planning tools available to meet those objectives (including zoning and joint development opportunities), and develop ownership from all stakeholders in TOD projects.

This report presents generally accepted definitions for TOD and joint-development TOD. If you are involved in a TOD project at a RTA station, taking these guidelines into consideration can help create very successful communities.

What is RTA?

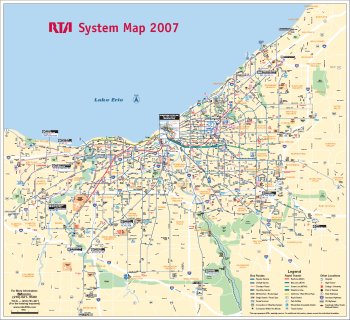

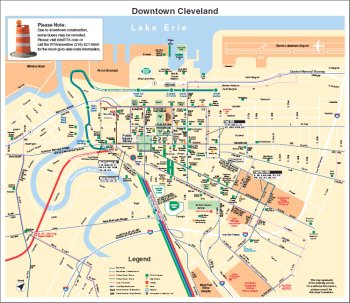

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) operates transit services for a 458-square-mile service area (see Figure 1 and Figure 2), including 59 municipalities and 1.4 million people. The services include buses, circulators, light rail, heavy rail, paratransit, and parking facilities, providing a total of 57 million passenger trips in 2005.

RTA connects the residents, employees, shoppers, and visitors of the Greater Cleveland region to the key trip generators within the City of Cleveland and throughout the area. The result is a mobile population that has choices for which travel mode to take to work downtown, to shop at more than 30 major commercial destinations, to explore at the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame, to travel from Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, or to see the Indians play at Jacobs Field. This modal choice supports the RTA’s overall mission to “enhance the quality of life in Greater Cleveland by providing outstanding, cost-effective public transportation services.”

Figure 2 RTA Downtown Cleveland System Map

What is Transit Oriented Development?

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) is commonly defined as mixed-use development designed to maximize access to, and promote use of, public transportation, with an emphasis on pedestrian circulation and accessibility. Typical elements of this design strategy include:

- Elevated densities – Increased population and employment densities place more potential riders within walking distance of transit stations/stops;

- Mixed-uses – Retail, office, residential, and public space promote concentrations of public activity around transit station/stops, increasing the physical and cultural prominence of transit in the community, as well as facilitating trip chaining linked to transit (i.e., stopping at a dry cleaners or day care facility on the way to the train during a morning commute, instead of making separate trips); and

- Pedestrian orientation – Placing daily goods and services, as well as recreational destinations, within walking distance of residents reduces incentives for car ownership and use, supporting transit use for commuting and other regional travel; orienting building entrances toward transit stops.

TOD has been promoted for decades in the United States as a means of promoting smart growth, expanding lifestyle options, boosting transit’s share of trips (especially commuter trips), and revitalizing neighborhoods. It is promoted as a means of redressing a number of the ill effects attributed to urban and suburban sprawl, including traffic congestion, air pollution, open space consumption, and a diminishing sense of civic connection in modern residential communities.

TOD's clustered mixture of land uses and elevated density levels, all in close proximity to transit options, offer a stark alternative to the traditional forms of development associated with sprawl. Its unique combination of dense, walkable surroundings and mobility options beyond private automobile use, has proven appealing to a number of growing demographic segments in the United States, especially singles, childless couples, “emptynesters,” and the soon-to-be-retiring “baby-boom” generation.

More recently, steady increases in both fuel costs and commute times across the country have increased interest in mobility options among all demographic groups. Several recent Federal initiatives have explicitly sought to promote TOD:

- New transit joint development policies, including a more permissive interpretation of Federal common-grant rules;

- Criteria for the Federal Highway Administration’s “New Starts” program that explicitly favor coordinated transit and land use in evaluating proposals for major capital investments in transit; and

- The Location Efficient Mortgage (LEM) program, underwritten by Fannie Mae, that makes it easier to qualify for a loan to purchase a home situated near transit.

Today, TOD projects are becoming more and more common throughout the country. A recent survey of transit authorities1 identified more than 100 TOD projects that have been developed, or are in the planning stages. The vast majority of these are located in or around large cities with rail transit service, with San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Portland among the cities with the greatest amount of active or completed TOD projects.

Expansion of existing transit systems and implementation of new systems across the country has added further momentum to the TOD movement, often by allowing cities to place transit services within districts where residential growth is strongest. New rail or bus rapid transit (BRT) systems are planned or under construction in all but three of the 30 largest U.S. metropolitan areas, including the Euclid Corridor Transportation Project Silver Line in Cleveland.

TOD is commonly located outside of city centers, in both inner-ring and outer suburbs. TOD tends to produce development of modest scale, though with residential densities well above suburban norms (20-30 dwelling units per acre compared to 5-6). These projects also incorporate a mixture of land uses, the most common components of which include:

- Mid-rise office buildings with street-level retail;

- Residential townhouses and condominiums;

- Restaurants and entertainment destinations; and

- Civic spaces and buildings such as plazas and libraries.

Figure 3 Bethesda Row Station Area Project, Bethesda, Maryland

What is Joint-Development TOD?

One of the most highly touted strengths of TOD is its potential for supporting increased transit use and compact land use patterns. The most direct means for capturing this potential is joint-development TOD – private development on, above, or adjacent to a transit authority’s property.2 The basic strength of this public-private coordination is that direct public investment and support makes TOD more attractive to profit-reliant developers, while direct involvement allows public authorities to shape projects around civic goals.

Just as importantly, joint-development offers tremendous potential to capture some of the value that transit services add to adjacent and surrounding real estate. Competition for public money is, and will likely always be, intense. TOD value capture can provide the means to help fund transit projects, by sharing in the real estate benefits of transit access.

The most common form of joint-development is the leasing of ground space or air rights on or above authority property. Following changes to FTA rules in 1997, sales of such rights and space have gained favor as well. Prior to 1997, authorities entered into unsubordinated long-term leases because they would have had to repay the federal treasury upon the sale of land purchased with FTA funds. Lease revenues, on the other hand, could be retained by the authority.

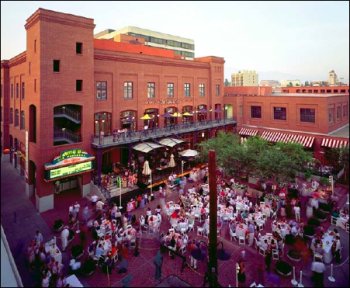

Figure 4 Joint Development at Mockingbird Station, Dallas, Texas

Many developers and investors, however, strongly preferred outright ownership to lease agreements. The FTA’s new joint development policies allow an authority to sell land and keep the proceeds, so long as they are used to support the authority’s mission of providing transit service. Since this change, many authorities have shifted to fee-simple sales, attracting stronger developer interest as a result. This has increased the pool of developers responding to RFPs and has made recent joint development deals generally more remunerative. In addition to service improvements and maintenance, the new FTA policies allow transit authorities to place property/air rights sales revenue into a revolving fund to support additional TOD activity.3

Other forms of joint-development include:

- Sharing of operating costs such as ventilation systems, utilities, and parking facilities between a transit station and adjacent development;

- Station connection fees; and

- Sharing construction costs (foundations, parking facilities, and construction staging areas) between station and adjacent development.

A large number of players are often involved in many TOD projects. At a minimum, joint development involves one transit authority, one local government, and one developer. Overlapping jurisdictions and service areas can add additional parties, as can the need for multiple lenders and investors beyond those directly involved. Comprehensive public involvement, a crucial component of TOD planning that should be initiated as early as possible, adds local advocacy groups, business organizations, neighborhood associations, and other stakeholders to the mix.

This large number of players in TOD projects creates numerous logistical challenges, first and foremost of which is creating a coherent vision and effective program for its achievement. No single player can, or should, completely set the agenda. Consequently, parties frequently focus narrowly on their perceived role and, even when a broad coalition of direct and indirect participating parties is engaged, the collective thinking fails to comprehensively address the many mutually supportive benefits offered by TOD. Figure 5 illustrates the variety of sometimes conflicting priorities that stakeholders bring to the table of a potential TOD project.

Figure 5 Stakeholders and Their Priorities

| Stakeholders | ||||||

| P r i o r i t i e s | Transit Authority | Riders | Local Residents | Local Government | Federal Government | Developer/Lender |

| Maximize Fiscal Return on Land | Ample Free Parking | Real Property Values | Maximize Tax Revenue | Protect Public Interest | Maximize Return on Investment | |

| Maximize Ridership | Improved Service and Access | Minimize/Reduce Traffic | Foster Economic Growth | Control Use of Investments | Minimize Risk | |

| Capture Long Term Value | Mobility Choices | Mobility Choices | Serve Constituents | Ensure Long Term Value | ||

| Pedestrian Access | Access to Transit, Services, and Jobs | Expand Tax Base | ||||

| Increase Local Destinations | Community Livability | |||||

| Expand Tax Base | ||||||

Source: Dittmar, Hank and Gloria Ohland. The New Transit Town; Island Press, 2004.

Why Transit Oriented Development?

Transit Oriented Development has enormous potential to help the Greater Cleveland area redevelop as a more economically vibrant, livable community, while increasing transit ridership, and reducing vehicular congestion on area roadways. Increasing the number of people who live and work within walking distance of RTA service is one of the most effective ways to increase ridership. TOD also brings broader benefits to the community, including other public sector entities, citizens, private enterprises like employers and developers, and the regional and global environment. These benefits have been studied extensively, and some of the most important advantages include:

Benefits to citizens of the region:

- Increased mobility choices, including the option to walk, bicycle, drive and take transit more easily to more destinations;

- Reduced household transportation costs, including the option to own fewer cars and take more trips by cheaper modes such as walking;

- Improved access to shopping, services, and recreational and cultural opportunities;

- Ability to live, work and shop within the same neighborhood;

- Increased homeownership rates or more adequate housing, especially among lower income groups;

- Improved access to public spaces, including parks and plazas;

- Better health and public safety, including reduced pollution-related illnesses, increased physical activity, and reduced traffic accidents;

- Choice among a diversity of housing types that reflects the regional mix of incomes and family structures;

- Improved air quality; and

- Higher productivity of employees through reduced stress factors and useable commute time.

Benefits to public authorities, local governments, and RTA:

- Increased transit ridership;

- Reduced auto use and auto ownership, and the resulting lower demand for parking and roadway expansions;

- Reduced community spending on streets and highways, and therefore lower taxes or increased community services;

- Higher tax revenues from increased retail sales and property values;

- Increased farebox, ground lease and/or joint development revenue;

- Increased transit service resulting from these stable, on-going revenue sources;

- Enhanced local community environment;

- Station areas that can serve as destinations as well as origins, thereby balancing peak loads;

- Spatial and financial efficiencies of shared facilities; and

- Increase transit network efficiency by generating reverse-commute and off-peak trips.

Benefits to private entities (e.g. employers, developers):

- Shorter and more predictable commute times, increasing the attractiveness of a work site to employees and improving employee morale;

- Decreased congestion;

- Better economic health related to employment and income generated at TODs;

- Higher return on investment for developers;

- Lower development risk and costs resulting from mix of uses and variety of housing types (affordable housing, rental units etc.); and

- Improved housing availability attracts wider range of employees to work in the Cleveland region.

Benefits to the regional and global environment:

- Improved air quality and reduced gasoline consumption;

- Preservation of farmland and open space;

- Reduced traffic and air pollution;

- More suitable regional and subregional balance between jobs and housing; and

- Enhanced regional identity.

Planning Initiatives at RTA

RTA’s Community Planning Initiatives

The first and foremost way to achieve transit goals in development is by the use of solid design principles. Most RTA transit issues are those of connectivity and form. If those are part of the design effort, there will be integration. Items such as sidewalks, where the building front door exists, and how pedestrians or heavy vehicles (e.g., buses) can use the site are essential items.

In that vein, RTA relates to communities in a myriad of ways. When designing an RTA passenger facility such as a rapid station or transit center, RTA engages the community stakeholders in the design of the building. This process includes residents, neighborhood groups, and stakeholders in a number of meetings and charettes to meet community needs. The facilities include good design elements that complement the built environment and also connect pedestrians and bicycle riders to it.

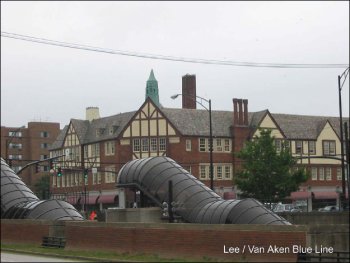

Rapid transit stations provide an additional opportunity for RTA to engage the community in preparing a station area plan that locates the station elements such as parking, building entrance, and related amenities along with addressing land use issues in the surrounding area. In those cases RTA, in cooperation with the community, can promote land uses around the station that complement the community and maximize the transit connection. RTA is actively working on such plans at the Lee/Van Aken Rapid Transit Station, the E. 120 Station, the Puritas Station and will soon begin planning at the University-Cedar Station.

RTA’s Transit Waiting Environments (TWE) initiative offers guidance to project sponsors on the types of amenities that could possibly be incorporated into existing bus stops. This initiative seems to be particularly useful when communities are undertaking streetscape projects. It provides a list of amenities that can be installed during improvement projects to enhance the public realm and makes the transit stop a more attractive and functional place in the community. RTA has worked with the City of Lakewood, Euclid, and Cleveland along Detroit and Lorain Avenues to encourage transit orientation. For more information on TWE visit http://www.cudc.kent.edu/projects_research/projects/TWE_Report.pdf.

For areas having less public transit service, usually the less-densely populated outlying areas of Cuyahoga County, RTA hopes that project sponsors will invite its participation. Jointly discussing in advance how new development and possible transit service enhancements can best be coordinated, is the most effective way in order to encourage the use of public transit. To the greatest extent possible, transit-supportive land use planning and zoning is encouraged, but RTA believes local officials must initiate this. RTA also welcomes any opportunity to comment on draft plans and zoning and advise public officials on ways that public transit can best be incorporated into them.

Figure 6 Lee/Van Aken Blue Line Rapid Transit Station

RTA’s TOD Goals and Initiatives

RTA’s has initiated planning for TOD projects, most notably at 6611 Euclid Avenue and 1950 E. 66th Street in the Midtown area of the City of Cleveland (Figure 7 and Figure 8), and is also preparing a site at 4501 – 4701 Euclid Avenue for a future TOD initiative (Figure 9).

TOD Goals

RTA has established goals for pursuing this type of development which include, but are not limited to, creating:

- High quality private or public development that is sensitive to the existing built environment;

- Development that promotes and enhances transit ridership by planning uses that are “transit-oriented” and that provide maximum linkages between transit stations and the development for transit patrons, pedestrians, and bicycles;

- Reduction in auto use and congestion through encouragement of transit-linked development;

- Value to RTA based on a fair market return on public investment, future revenue streams, additional taxes, and reduction in the cost of the site construction for RTA;

- Development that maximizes the highest and best use of the real estate based on land use and economic development goals of the surrounding community and conforming to local and regional development plans; and

- Value to the neighborhood, the developer and RTA through intensive, high quality development.

Figure 7 Proposed RTA TOD Site, 661 Euclid Avenue

Figure 8 Euclid Avenue Corridor

Figure 9 Future RTA TOD Site at 4501-4701 Euclid Avenue

Strategies

To achieve these goals, RTA will undertake the following strategies:

- During the station and facility planning efforts RTA will work collaboratively with the stakeholders and local jurisdictions as appropriate adjacent its transit facilities to proactively promote and develop locations, plans and designs that maximize the benefits of the transit linkage. This effort will include community involvement and participation in the planning process.

- Work collaboratively with adjacent landowners and stakeholders to maximize uses and linkages to transit facilities.

- Solicit proposals for transit-oriented joint development through a competitive selection process where feasible in terms of the market and availability of land. These solicitations and projects must meet all FTA federal requirements and State, RTA regulations. The attachment lists requirements for the solicitation package.

- Accept proposals for joint development projects as received. These proposals must meet all applicable joint development requirements including those of RTA, the State of Ohio, and FTA.

- Request funding for Joint Development activities as part of RTA capital program as appropriate. These activities must be consistent with FTA regulations and requirements.

- Complete an assessment for RTA owned facilities to maximize development opportunities through adjacent development activities and leasehold interests within RTA facilities. RTA real estate will be viewed as the asset it is in facilitating the goals of this policy.

The Euclid Corridor project will involve a complete building-face-to-building-face reconstruction of Euclid Avenue between Public Square and University Circle that includes:

- Exclusive bus lanes;

- One lane in each direction for auto traffic;

- Pedestrian zone enhancements which encourage transit usage (new sidewalks, passenger shelters at center median stations, pedestrian lighting, street trees and tree lawns);

- Roadway reconstruction and design to create consistent curb lines and numbers and widths of travel lanes, upgraded street lighting, and crosswalks at intersections designed to clearly identify pedestrian zones;

- Traffic signal equipment installation on Euclid Avenue and on intersecting streets, as necessary, to provide priority to RTA vehicles operating on Euclid Avenue; and

- The installation of pedestrian and vehicular signage to clearly identify the availability of transit service.

RTA Support of Community-Based TOD Initiatives

RTA recognizes that throughout northeastern Ohio, most communities take the lead in land use planning and guiding development. Where RTA already has a major presence (i.e. busy bus or rapid transit lines with stops and stations located near major activity centers), RTA offers to participate in the planning for the revitalization of the areas surrounding the transit facilities.

Examples include improving selected transit waiting areas in Cleveland, Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights as part of streetscape projects initiated by those municipalities. In Euclid, RTA has been invited to participate in the City's downtown revitalization planning efforts, where new street patterns will affect bus routes and new development offers a chance to coordinate a more efficient bus layover location and more convenient and comfortable passenger boarding locations. Another example is the City of Westlake, a suburban municipality focused on developing a new shopping mall. The City and developer created Crocker Park, a "lifestyle center" reminiscent of a traditional small town downtown district. Provisions were made for RTA buses to easily access Crocker Park, along with developer-designed/funded bus shelters.

RTA is also a willing partner/stakeholder in community planning and corridor planning processes. RTA will partner and participate as communities continue to plan for the future. Often times, RTA can assist in supporting these efforts. The county municipality or community development organization will, on its own and/or with funding from the region’s metropolitan planning organization, NOACA, plan to redevelop an area or travel corridor. When that area or corridor contains public transit bus or rapid transit lines and stops that could be affected, RTA prefers to jointly explore with the project sponsor, in advance of design and construction, how transit services and stops could be enhanced. This could involve short-term improvements like upgrading existing transit waiting areas or long-term improvements like focusing newly-developed or redeveloped around transit lines.

Where new TOD planning initiatives are being undertaken, RTA encourages adoption of zoning regulations that support TOD development. In 2004, MidTown Cleveland, Inc. and the City of Cleveland Planning Commission initiated planning for a Midtown Cleveland Mixed Use zoning overlay district. RTA offered technical assistance to help make the overlay zone more transit friendly around advanced transit facilities. The result is the Midtown Mixed Use District which is Transit Oriented Zoning overlay, a compact, high to promotes local economic activity in developments that are diverse, livable, sustainable, and enhance and maintain quality of life. The specific elements of the PTD District conform to the TOD Guidelines (discussed later in this report), including:

- concentration of retailing, personal and business services, as well as residential and cultural uses at a necessary intensity to efficiently be served by a mass transit system;

- Continuous, direct, convenient transit and pedestrian linkages, including walkways between principal entrances of buildings and to adjacent lots;

- Increased density/intensity by varying the types of residential and commercial units provided;

- Encouragement of the use of public transit by reducing parking requirements within the PTD and the provision of park and ride lots near advanced transit facilities where appropriate;

- Improved pedestrian environment with amenities, such as pedestrian lamps, awnings, canopies, benches, trees, and shrubbery;

- Protected pedestrians and cyclists from traffic using clearly designated crosswalks, buffering, shelters, lighting, and grade separations;

- Buildings oriented to make pedestrians comfortable, by minimizing walking distances, enhancing visibility and by clustering buildings;

- Attractive building facades including street-level display windows and varying setback;

- Parking situated to the rear of the structure with proper screening, or in a parking garage, which possesses storefronts on any side facing an urban corridor; and

- A minimized number of curb cuts/driveways.

In addition to the Midtown Mixed Use District, the Cleveland Zoning Code describes three other regulations which are consistent with TOD planning:

- Planned Use Development, which permits development of zones with greater flexibility for mixing uses than traditional requirements;4

- Live-Work Overlay Districts, which allow shared occupancy of space by residential uses in combination with work activities in suitable locations. These districts are intended to assist in revitalizing areas impacted by the presence of under-utilized and deteriorated buildings suitable for re-use as live-work space;5 and

- Pedestrian Retail Overlay (PRO) District, which supports the economic viability of older neighborhood shopping districts by preserving and emphasizing the pedestrian-oriented character of those districts.6

RTA is fully supportive of these community planning efforts and wishes to work with communities to create more of these districts throughout the region.

Recommended TOD Guidelines

The results of successful Transit Oriented Development are complete communities where land uses and transportation are mutually supportive, and populations that can live, work, play, and thrive in their neighborhood while still being connected to the opportunities throughout the region. For TOD to be successful, it must effectively and efficiently coordinate the various land use and transportation components. This section describes 14 guidelines for TOD projects; the following section describes these guidelines in more technical detail.

Land Use Keys

The simplest way to think about Transit Oriented Development is a lot of people comfortably living and working nearby each other, with lots of opportunities to interact each day. The first element of a TOD neighborhood is therefore a land use plan that allows many people to accomplish many, varied activities.

Mixed Uses Coupled with Density

By providing residential, commercial, recreational, and municipal space within a compact district, TOD neighborhoods offer people easy access to all the things they do every day: live, shop, work, and play. This proximity also offers the opportunity not to drive for each trip, which translates into fewer parking spaces needed, and more room for destinations that serve people instead of their cars.

The perfect mix and density of land uses around a transit station is not the same for every station; it depends on the needs and preferences of the surrounding neighborhood. A community-focused planning process should be used to identify these needs and preferences. A TOD project should include some mix of the following uses:

- A wide variety of residential choices, ranging from apartments and studious to single-family homes, with both rentals and owner-occupied units. Residential density within a half-mile radius of the station should be high enough to support healthy ridership.

- Small-scale commercial and office space throughout the neighborhood, with any large office buildings as close to the station as possible.

- Community services, including libraries, schools, childcare, and museums, especially with pedestrian connections to transit and other land uses.

- Public gathering spaces, including parks, plazas, and courtyards attract people and change a street to an active place. Ideally, these spaces should be versatile to accommodate different activities and groups. These places must be maintained and safe.

- Transit and parking facilities should accommodate retail or other active uses at the ground floor.

- No matter what uses are included, architectural character and a consistent scale are needed for new development to harmonize with existing buildings.

- Densities should be highest closest to the transit station and gradually step down further away. Parking provisions should be lower closer to the station.

Figure 10 Provide Public Gathering Places to Create an Active, Vibrant Location

Transportation Keys

Pedestrian Orientation

Whether a commuter is riding the train, a shopper is driving to a store, or a student is bicycling to school, every trip starts and ends as a walking trip. A TOD should provide a safe, welcoming pedestrian environment throughout the community, so that all travelers can walk along an interesting and safe route between their homes, offices, transit stops, or other destinations.

Figure 11 Building Frontages with Active Streetwalls and No Street-Facing Parking (Cambridge, MA)

- On main pedestrian routes, minimize the number of driveways, garage entrances, and dedicated turning lanes.

- Pedestrians need to feel safe when walking. Install bollards, trees, and other street furniture to protect pedestrians and buildings from errant drivers.

- Minimize streets widths in the station area to the smallest width needed to accommodate local travel speeds and emergency vehicle access.

Access and Circulation

One of the defining characteristics of TOD is availability of transportation options; this is what lets people to do all daily activities, without needing a car for every trip. Whether the neighborhood is served by train, bus, or light rail, service needs to be frequent and reliable. In addition, people need to be able to circulate within the area, so TODs must prioritize the needs of non-motorized modes.

- Frequent, reliable, all-day transit services must be provided along key corridors and serving key destinations, where population and job densities permit this.

- Bicycle networks should run throughout the TOD and directly to transit stations, with clear signage leading the way, and bicycle parking available throughout.

- Parking facilities should feed pedestrians onto primary pedestrian routes, should be located to promote retail opportunities along these routes, and should provide parking for both autos and bicycles.

- Sidewalks should be designed to exceed the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act and include street furniture (e.g., benches) and design features (e.g., human-scale street lights).

Figure 12 Parking Facilities Feeding Pedestrians Directly to Pedestrian Routes and Serving Both Autos and Bicycles

Technical Discussion of Recommended TOD Guidelines

Transit authorities play a crucial role in broadening the vision for, and raising the expectations from, TOD. This role includes, not only proactively seeking TOD opportunities at transit stations, but becoming, and remaining, directly involved in the planning and development process in order to extract the full spectrum of benefits TOD offers. The following design lessons provide valuable guidelines for framing future TOD projects.

Density

TOD generally requires a minimum of seven to fifteen residential units per acre in residential areas and 25 employees per acre in commercial centers, and about twice that for higher frequency transit, such as rapid transit or loop buses. Increased population and employment densities place more potential riders within walking distance of transit stations/stops and higher densities, especially residential densities are recommended depending on the type of transit serving the area (see Figure 13). Minimum residential densities of 12-25 dwelling unites per acre are becoming for common. These densities create adequate transit ridership to justify frequent service, and help create active street life and commercial activities, such as grocery stores and coffee shops, within convenient walking distance of homes and worksites. The greatest increase in ridership occurs when densities reach approximately 30 dwelling units per acre, which allow for premium services, like bus or rail rapid transit.

Figure 13 Minimum Residential Density Thresholds for TODs

Transit Mode | Minimum Dwelling Units per Acre |

| Basic Bus Service | 7-15 |

| Premium Bus Service | 15-18 |

| Light Rail Transit | |

| Distance:0-1/8 mile | 30 |

| 1/8-1/4 mile | 24 |

| 1/4-1/2 mile | 12 |

Source: Transportation Cooperative Research Program, Report 102: Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospect (2004).

Commercial land uses require acknowledgement of employment density as well as Floor to Area Ratio (FAR). Recommended FAR’s start at 0.35 for nonresidential activities in TODs, but are more frequently recommended at minimums of 0.5 to 1.0 for commercial developments without structured parking and at least 2.0 for developments with structured parking. Employment density of 25 jobs per gross acre (15,000 jobs within one half-mile) will support frequent, high capacity transit service. For light-rail service, employment densities of 50 jobs per gross acre are recommended.

High-frequency transit supports the development of high-density centers, which can provide accessibility and agglomeration benefits (efficiencies that result when many activities are physically close together), while automobile-oriented transportation conflicts with urban density because it is space intensive, requiring large amounts of land for roads and parking facilities. Large-scale park-and-ride facilities tend to conflict with TOD, since a rail station surrounded by large parking lots and arterials with heavy traffic is unlikely to provide the densities needed to generate sufficient transit demand. It is therefore important that such facilities be properly located, designed, and managed to minimize such conflicts.

Mixed-Uses

Traditional, or Euclidean, zoning separates land uses, sets density thresholds and minimum lot sizes, and usually contains explicit regulations such as bulk and height controls and minimum parking. With TOD, however, traditional zoning is often turned on its head (i.e., uses are intermixed, not excluded, and parking caps, rather than parking floors, are sometimes set).

To allow for TOD, a municipality can create a special TOD zone or change existing classifications. More common than either rezoning or new designations, however, is the creation of an overlay zone. As its name implies, an overlay zone is placed on the zoning map over a base zone. The overlay modifies, eliminates, or adds regulations to the base zone. Overlays provide for effective land-use control without increasing the complexity of the regulations. An example of this is the overlay zoning by the City of Cleveland in the Euclid Corridor.

Besides identifying unwelcome land uses, like automobile repair shops, TOD zones often specify activities that are permitted as-of-right. According to the Federal Transit Administration, joint development TOD projects are “commercial, residential, industrial, or mixed use developments that are undertaken in concert with transit facilities.”7 The uses included in a TOD community should generate trips throughout the day. This strategy takes advantage of unused transit supply in off-peak hours and results in routes that are more productive than in areas with traditional rush-hour peaks.

The following list presents a sample of land uses appropriate for inclusion in a TOD:

- Mid- to high- density residential;

- Retail stores;

- Banks;

- Private offices/professional businesses;

- Government offices;

- Schools (especially higher education);

- Child-care centers;

- Community facilities;

- Public space; and

- Entertainment complexes.

Pedestrian Orientation

Pedestrians who can access the land uses within a neighborhood are more likely to utilize those sites, including retail, parks, and transit. Placing daily goods and services, as well as recreational destinations, within walking distance of residents reduces incentives for car ownership and use, supporting transit use for commuting and other regional travel. The following recommendations outline the key design factors that focus development to pedestrians:

- Locate active uses that generate a higher number of daily trips on the first two floors. These should include retail and open space located in the first 15-20 feet of building height. Land uses that generate fewer trips should occupy higher floors (see Figure 14).

- Bring sidewalks up to the building line and prohibit parking from being located between the sidewalk and the building.

- Curb cuts are extensions of sidewalks. Design sidewalk-driveway interfaces to be identical to sidewalks (e.g. the sidewalk material and level should continue across the driveway). This alerts both pedestrians and drivers that they are traveling on a portion of the sidewalk.

- Install bollards, trees, and other street furniture to protect pedestrians and buildings from errant drivers.

- Sidewalks connecting the station or bus stop to key nearby intersections and destinations should be as short, direct, and visually unobstructed as possible.

- Sidewalks to the station or bus stop should be wide and smooth enough for wheelchairs and strollers, and lined with trees, lights and wayfinding signs.

- When designing pedestrian paths, remember that unlike cars, pedestrians can and do walk the shortest routes to their destinations (known as desire lines). If pedestrianways are not provided, walkers will create their own desire lines. Planners should anticipate the need for direct pedestrian paths.

- The less that pedestrians must go up and down (by staircase, elevator bridge, and tunnel), the more likely they will choose to walk.

- Buildings along sidewalks should open directly onto the sidewalk, with transparent ground floors and good views of the path from the upper floors.

- Continuous building frontages should be maintained along sidewalks by avoiding front and side setbacks, blank walls, and surface parking lots that face the sidewalk.

- Building entrances should be conveniently situated relative to transit stations/stops.

Figure 14 Active Uses on Ground Floor; Less Active Uses Above

- Sidewalks should be to at least five feet wide at all points.

- Install curb extensions (wider sidewalks) at all corners with on-street parking.

- Install pedestrian signals at all traffic signals.

- Actuate pedestrian phase at all times with traffic phase, e.g. not pedestrian actuated.

- Include Leading Pedestrian Intervals at all signals, thus allowing pedestrians to start ahead of traffic.

Access and Connections

Pedestrians must be able to easily access and traverse a site, for it to encourage pedestrian activity and, economic vitality. In order to discourage vehicular trips, TODs must prioritize the needs of non-motorized modes. The following provides a menu of options for promoting non-motorized transportation:

- Reduce vehicular roadway lane widths and rededicate the reclaimed space to provide or widen sidewalks, crosswalks, paths, and bike lanes.

- Reduce the number of conflict points between motorized and non-motorized modes. Where conflict points are unavoidable, ensure non-motorized modes have clearly delineated pathways and drivers are aware of their responsibility to share the road.

- Increase road and path connectivity, with special non-motorized shortcuts, such as paths between cul-de-sac heads and mid-block pedestrian links.

- Adhere to and exceed the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

- Include street furniture (e.g., benches) and design features (e.g., human-scale street lights) without blocking traveler’s “desire lines” (paths which travelers use, whether designated or not).

- Guide motorized modes to operate at appropriate speeds and along appropriate routes for each location the community character.

- Provide bicycle parking and amenities (lockers, showers, access routes) to connect with all transit facilities.

- Create a Multi-Modal Access Guide, which includes maps and other information on how to walk and cycle to a particular destination.

Figure 15 compares various modes in terms of their priority (based on whether they help provide basic mobility or tend to be more recreational uses) and performance (size and speed). TOD accessways should be prioritized based on the performance and value of each mode. Below are examples:

- Higher-priority modes should have priority over lower-priority modes. For example, recreational modes (such as skateboards) should yield to modes that provide basic mobility (such as walking and wheelchair users) if conflicts exist.

- Lower-speed, smaller modes should be given priority over higher-speed, larger modes. For example, bicycles should yield to scooters, and scooters should yield to walkers.

- Maximum speeds should be established for each mode, based on the physical design of the facility (i.e., some facilities may only accommodate 10 mph cycling, while others can accommodate 15 mph cycling). Maximum allowable speeds should decline as a pedestrian facility becomes more crowded or narrower.

- If facilities cannot accommodate all potential modes, higher-priority modes should be allowed and lower-priority modes should be required to use roadways. For example, cycling and skating may be allowed on pedestrian facilities at uncrowded times and locations, but not at busy times and locations.

- Special efforts should be made to accommodate a wide range of users (including cyclists, skaters, and runners) where there are no suitable alternative routes (e.g., adjacent roadways are unsuitable for such modes).

Figure 15 Non-Motorized Facility Users Compared

User Type | Speed | Size (Width) | Maneuverability | Risk to Others | Priority |

| People standing or sitting | None | Low | None | Minimal | High |

| Walkers | Low | Narrow | High | Minimal | High |

| Walkers with children | Low | Medium to large | Medium to low | Moderate | High |

| Walkers with pets | Low | Medium to large | Medium to low | Moderate to High | Medium |

| Human powered wheelchairs | Low | Medium | Low to medium | Minimal | High |

| Motor powered wheelchairs | Medium | Medium | Medium | Moderate | High |

| Joggers and runners | Medium to high | Narrow | Medium | Moderate | Medium |

| Skates, skateboards and push-scooters | Medium | Medium | Medium | Moderate to High | Low |

| Powered scooters | Medium | Medium | Medium | Moderate to High | Medium |

| Handcarts, wagons and pushcarts | Low | Medium to large | Low to medium | Moderate to High | Medium |

| Human powered bicycle | Medium to high | Medium to large | Medium to low | Moderate to High | Medium |

| Motorized bicycle | High | Medium to large | Medium to low | Moderate to High | Low |

| Equestrians | Medium to high | Large | Low | Moderate to High | Low |

Source: Victoria Transport Policy Institute, 2005

TOD Site Survey Worksheet

While TOD guidelines are valuable resources, RTA recognizes that they are limited if they cannot be applied to site-specific locations. In an effort to provide the community with a mechanism for applying the guidelines, Figure 16 outlines the existing conditions for each site will need to be documented. These conditions can then be applied to the minimum requirements and ideal conditions, to determine what is lacking in implanting a TOD project. The categories of conditions to be determined are based on the guidelines described above: density, land uses, pedestrian orientation, accessibility, and connectivity. In addition, the zoning framework guiding site development is also addressed.

Figure 16 TOD Site Survey Worksheet

Question | Actual | Minimum Required | Ideal Condition | Meets Minimum? | |

| How many residential units per acre? | for Basic Bus | 7 | 14 | ||

| for Premium Bus | 15 | 18 | |||

| for LRT 1/4-1/2 mile | 12 | ||||

| for LRT 1/8-1/4 mile | 24 | ||||

| for LRT 0-1/8 mile | 30 | ||||

| What is the employment density per acre? | 25 | 50 | |||

| What is the FAR in non-residential areas without structured parking? | 0.5 | 1.0 | |||

| What is the FAR in non-residential areas with structured parking? | 1.0 | 2.0 | |||

| Is a large-scale park & ride facility located adjacent to the transit station (if applicable)? | N | N | |||

| How many parking spaces per residential unit? | 1.3 max | 1.0 or fewer | |||

| How many parking spaces per 1,000 sq ft nonresidential uses? | 3.0 max | 2.0 or fewer | |||

| Is the price of residential parking unbundled from residential leases or sales prices? | Y | Y | |||

| Are all non-residential parking spaces shared among different uses? | Y | ||||

| Are all non-residential parking spaces charged for by the hour, or do employers offer parking cash-out? | Y | ||||

| Has the site been nominated for rezoning or overlay zoning to modify base zoning? | Y | Y | |||

| In general, does the area contain a mix of residential, retail and office uses? | Y | Y | |||

| Does the site contain three or more of the following land uses: | Y | ||||

| Mid to high-density residential | Y | ||||

| Retail stores | Y | ||||

| Banks | Y | ||||

| Private offices/professional businesses | Y | ||||

| Government offices | Y | ||||

| Schools | Y | ||||

| Child care centers | Y | ||||

| Community facilities | Y | ||||

| Public space | Y | ||||

| Entertainment complex | Y | ||||

| Percentage of frontage dedicated to openings (windows and doors) compared to blank space? | 50% | ||||

| Percent of space used for active uses (i.e. retail and open space) between 0' and 20'? | 75% | 100% | |||

| What is the average block perimeter? | 1600' max | 1000' - 2000' | |||

| Do sidewalks extend up to building line and an greenspace? | Y | ||||

| Is surface parking located between sidewalk and building? | N | ||||

| Do curbcuts prioritize pedestrian movements? | Y | ||||

| Percent tree canopy at full growth over street area or minimum tree spacing standard? | 40% or 40' | 75% or 25' | |||

| How many feet wide are sidewalks at narrowest point? | 5 | 16 | |||

| Does the sidewalk widen at corners with on-street parking through use of curb extensions? | Y | ||||

| Are pedestrian signals present at all traffic signals? | Y | ||||

| Are pedestrian signals actuated with regular auto traffic cycles? | Y | ||||

| Are leading pedestrian intervals present at all traffic signals? | Y | ||||

| Are there non-motorized paths connecting site destinations? | Y | ||||

| How wide are roadway lanes? | 12' max | 10' | |||

| At conflict points between pedestrians, bicycles, and cars, are pathways clearly delineated? | Y | ||||

| Do pedestrian facilities adhere to Americans with Disabilities Act requirements? | Y | Exceed required | |||

| Are design speeds set at or below 30 mph? | Y | ||||

| Are bicycle parking and amenities located at transit facilities? | Y | ||||

| Does the site accommodate a variety of non-motorized users, from pedestrians to recreational activities like cycling and skateboarding? | Y | ||||

References and Bibliography

Books, Reports, and Documents

The New Transit Town, Hank Dittmar and Gloria Ohland, Island Press, 2004.

Report 102: Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospect, Transportation Cooperative Research Program, (2004).

Policy on Transit Joint Development, Number 62 12266, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Register: March 14, 1997 (Volume 62, Number 50).

Informational Resources

Victoria Transport Policy Institute - www.vtpi.org

Transit Cooperative Research Program - www.tcrponline.org

Urban Land Institute, Development Case Study Library - uli.org/publications/case-studies/

Transit Authorities

Boston: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority - www.mbta.com

Dallas: Dallas Area Rapid Transit - www.dart.org

District of Columbia: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority- www.wmata.com

Portland: Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon - www.trimet.org

San Jose: Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority - www.vta.org/projects/tod.html

APPENDIX

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION GUIDANCE AND REGULATIONS FOR TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT AND FEDERALLY FUNDED JOINT DEVELOPMENT IMPROVEMENTS

FTA Circular 9300.1A: Capital Program: Grant Application Instructions (10-01-98) (superseded by FTA circular 9300.1B (11-01-08)

Proposed Joint Development Checklist

Proposed Certificate of Compliance

1 Transportation Cooperative Research Program, Report 102: Transit-Oriented Development in the United States: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospect (2004).

2 Ibid.

3 Dittmar, Hank and Gloria Ohland. The New Transit Town; Island Press, 2004.

4 http://library.amlegal.com/nxt/gateway.dll/Ohio/cleveland_oh/partthreelandusecode/partiiiblandusecode-zoningcode/titleviizoningcode/chapter334-plannedunitdevelopmentoverlay?f=templates$fn=default.htm$3.0$vid=amlegal:cleveland_oh$anc=JD_Chapter334

5 http://library.amlegal.com/nxt/gateway.dll/Ohio/cleveland_oh/partthreelandusecode/partiiiblandusecode-zoningcode/titleviizoningcode/chapter346-live-workoverlaydistricts?f=templates$fn=default.htm$3.0$vid=amlegal:cleveland_oh$anc=JD_Chapter346

6 http://library.amlegal.com/nxt/gateway.dll/Ohio/cleveland_oh/partthreelandusecode/partiiiblandusecode-zoningcode/titleviizoningcode/chapter343-businessdistricts?f=templates$fn=default.htm$3.0$vid=amlegal:cleveland_oh$anc=JD_343.23

7 Federal Transit Administration, Policy on Transit Joint Development, Number 62 12266, Federal Register: March 14, 1997 (Volume 62, Number 50)